Famously known as Neue Sachlichkeit, the New Objectivity movement was one of the greatest movements of the 20th century. What did the movement entail, and what are the characteristics of art from the New Objectivity movement? In this article, we will discuss the aim behind the movement and its influence on the development of German painting and post-expressionism. Keep reading for more about this matter-of-fact movement!

Table of Contents

Among the many criticisms against Expressionism in the 20 th century, the New Objectivity movement was perhaps the most impactful in advocating for a return to non-romantic forms of representation and the abandonment of idealism. Before the First World War, Expressionism was among the most dominant movements of the time, which alongside Futurism, led to many artists opting for anything but objectivity. In Germany, Expressionism was entrenched in almost all aspects of culture, including theater, literature, architecture, and dance.

Red Horse (1932) by Ewald Schönberg; Ewald Schönberg (1882–1949), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

So, what was the German New Objectivity movement? The movement was better known as the Neue Sachlichkeit in Germany with other translations describing the movement as “New Sobriety” or the “New Resignation”. In the word Sachlichkeit, “sache” translates to the English terms “fact” or “object”, while Sachlich translates to “matter-of-fact” or “practical”. The movement itself originated in the 1920s and was established by the German historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, who was also a director at the Kunsthalle Mannheim.

In 1925, Hartlaub introduced the term to showcase the works of artists, whose works reflected a new genre in art style understood as post-Expressionist. Among this group were artists such as Otto Dix, Jeanne Mammen, and Christian Schad, who were considered to be the pioneers of New Objectivity art. This group of artists all rejected the foundations of Expressionism, which was built on the self-involvement of the artist and their emotions. The intellectuals of Weimar also issued a public call to promote the rejection of idealism and romanticism inherent in Expressionism.

Similarly, Futurists also believed that Expressionism was useful in helping artists broadcast the societal concerns and anxieties about the coming war while providing them with a platform for forging individual identities and highlighting the sense of alienation in a rapidly modernizing world.

In painting, Neue Sachlichkeit was embedded as an attitude that mirrored the society in Weimar, Germany. In essence, the German New Objectivity movement was a collective desire to return to a world view of practical engagement with the rest of the world and adopt the all-business outlook, which was perceived as an “American” approach in Germany. Once the Weimar Republic came to an end in 1933, so did the movement, as it also coincided with the beginning of Nazi rule.

According to the art historian Dennis Crockett, the aim of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement was to drive a more profound political agenda than its predecessor Expressionism. The movement emphasized the hard facts of the day driven by usefulness, functionality, and professional conscientiousness. While many people confuse the meaning of the term Neue Sachlichkeit and its translation of the “New Resignation”, scholars such as Crockett have made it clear that although the term may have been construed with the sense of resignation found in the era of the great socialist revolution, the Neue Sachlichkeit movement was propelled by left-leaning intellectuals who wished to adapt to the social order found in the Weimar Republic.

What spurred the growth of the German New Objectivity movement was the many rising criticisms against the former Expressionist groups and their lack of true and effective impact on driving political impact. Strong criticisms began in Dadaism with early pioneers of Dadaism convening in Switzerland, which was a war-neutral country, where the Dadaists communed to establish their aim of creating art that was to be used as tools for cultural and moral protests. The Dadaists wanted to convey their political frustrations and encourage action in society, which they believed Expressionism had fallen short of accomplishing.

Myself: Portrait – Landscape (1890) by Henri Rousseau; Henri Rousseau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Another influential criticism of Expressionism was by the dramatist Bertolt Brecht, who thought of the movement as too superficial and constrained. He made many references to the fact that there were more ideas, however, the ideas were not new, similarly, in theater, he also highlighted the desire for more drama, yet there was no real drama to the movement. Many critics of the Expressionist movement were considered to be conservative, which saw New Objectivity and the return to order thrive after the effects of the war became evident.

Across Europe, Neoclassicism was pioneered by many modernists, located especially in Italy, who wished for a return to order and moved away from abstraction. Between 1919 and 1922, most German artists were not aware of the upcoming trends in French art due to the travel restrictions at the time. One of the most prominent influences in the German New Objectivity movement was Henri Rousseau, who passed away in 1910 but his legacy was felt years later in New Objectivity art.

Publications such as Valori Plastici deeply influenced many German artists who drew inspiration from the magazine and its exhibition of Realist photographs and paintings by Italian artists.

Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub first used the term New Objectivity to introduce a show with works of German artists following the hype of Expressionism. He also characterized the movement as defined by two main tendencies known as left and right wings. The verists were recognized as the left-winged group, who strived to represent existing experiences with their distinct “fevered temperature and tempo” while highlighting the objective forms of contemporary facts. Many verists under New Objectivity used Realism to highlight the elements of life that were sordid and unappealing.

Political poster art by John Heartfield in an exhibition (2009); MJ Klaver, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Verist art was considered to be raw, heavily satirical, and provocative. Two of the most profound verists included Otto Dix and George Grosz, who helped evolve the idea of abandoning pictorial conventions and championed “satirical hyperrealism”. Such examples of works that embody satirical hyperrealism include the photomontage works of John Heartfield, whose collage compositions merge art and reality and imply the notion that the act of recording facts extends beyond surface appearances. The classicists referred to the right-winged artists, who sought to “embody the external laws of existence” in art. Artists who worked in Magical Realism were understood to be classicists and were best captured in the works of artists like Franz Roh. Roh’s establishment of the term “Magical Realism” was thought to encapsulate the whole of Neue Sachlichkeit and presented the magic of the real world through fantastical and strange depictions of reality.

Satire was used as a tool to portray the “behind-the-scenes” worlds of reality that also incorporated cartoon aesthetics for satirical scenes. Portrait paintings also highlighted certain features of subjects or objects that were viewed as defining features of the sitter. Visual languages with clinical precision in painting appeared in works by artists such as Christian Schad who portrayed reality in a way that alluded to an empirical detachment from the subject and an in-depth knowledge of it. His works were described as displaying a sharp artistic perception that could “cut beneath the skin” and introduced elements of unconscious realities and psychological tension.

Below, we will examine a few of these key artists of New Objectivity, as well as examples of their work that will help you gauge the visual languages of the movement.

| Artist Name | Max Carl Friedrich Beckmann |

| Date of Birth | 12 February 1884 |

| Date of Death | 27 December 1950 |

| Nationality | German |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, New Objectivity, and Expressionism |

| Mediums | Painting, writing, sculpture, printmaking, and draftsmanship |

Max Beckmann was one of the most famous artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, whose expressive images of modern life left an impact on the visual language of the movement. Beckmann was closely associated with Expressionism and academicism in his early career and later dedicated himself to New Objectivity. He was best known for his “scathing” visual criticism during the interwar years. During the First World War, Beckmann served as a medical officer and witnessed, firsthand, the impact of war, which subsequently influenced his artistic style.

Max Beckmann (1928) by Hugo Erfurth; Hugo Erfurth, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

His art began to take on a more expressive approach that reflected his critical engagement with the “magic of reality” in painting. He was opposed to abstraction and was skilled at creating intricately layered narrative paintings that showcased his mastery of shadow and color. Beckmann also drew from images in reality combined with allegory to convey his unique understanding of his context.

He created more than 85 self-portraits that reflected his pursuit of self-knowledge and desire to establish his autonomy.

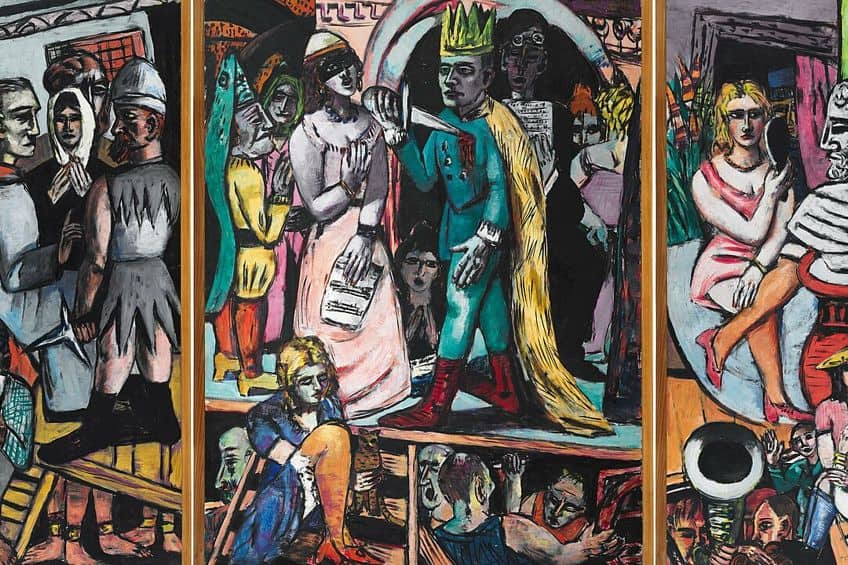

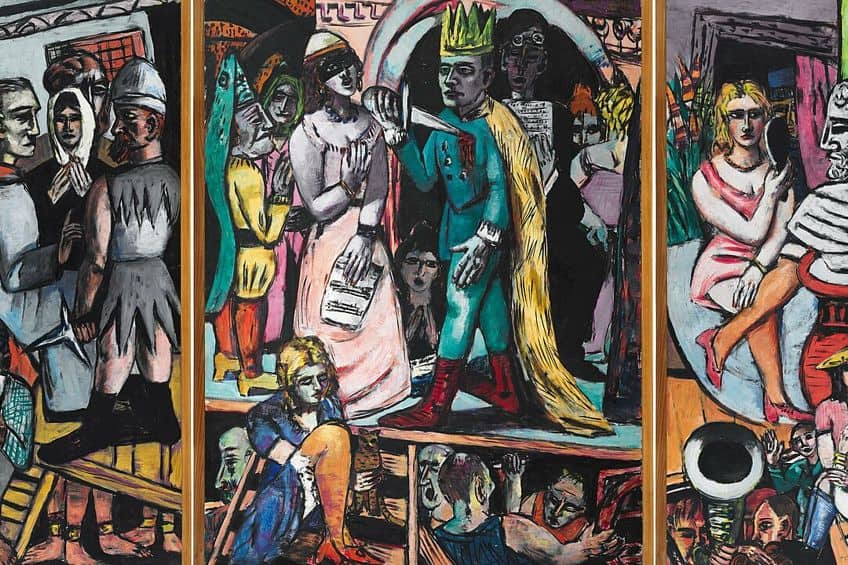

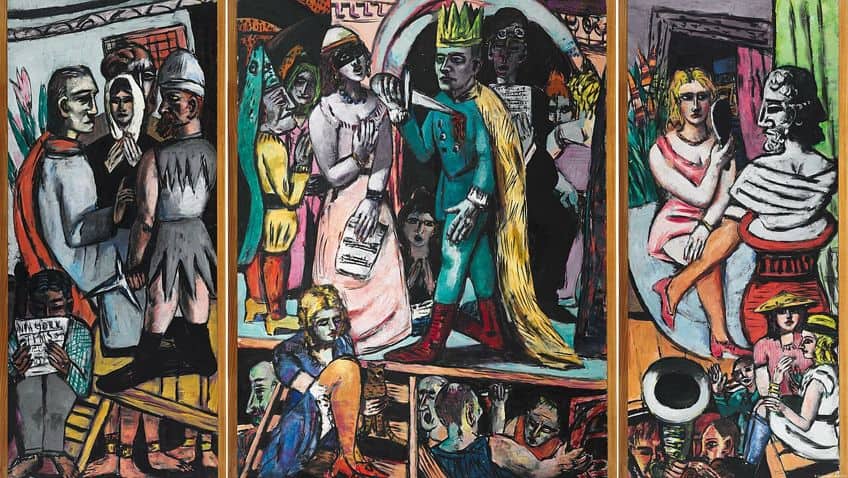

| Date | 1932 – 1935 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | Three panels: 215.3 x 99.7 (two side panels) and 215.3 x 115.2 (central panel) |

| Where It Is Housed | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Departure is one of Beckmann’s most well-known works from New Objectivity that was created before the Nazi dictatorship came into power and just after the artist was deposed from his position as a teacher in Frankfurt. He publicly claimed that he was apolitical in many of his lectures, however, his anxiety about the coming future was evident in many of his works that showcase the fear and stress caused by the cruelty of the Nazi era. Departure represents Beckmann’s first triptych artwork that highlights some of the key moments in a larger narrative to draw attention to the theme of perseverance.

Departure (1932 – 1935) by Max Beckmann; Max Beckmann, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On the left panel, Beckmann highlights a torture scene with several figures whose hands are bound and appear to be forced to commit violent acts. The side panels on either side portray the artist’s vision of the brutality and violence inflicted by people on other people, which casts a dark vision of humanity, or better, lack thereof. The middle panel depicts a woman tied to a man who hangs upside down. This scene represents the possibility of salvation through the scene of a family in a wooden boat floating out to sea.

A fisher king is seen casting his blessing over the scene while the mystery of the world is represented by an ominous figure of a hooded man who holds a fish.

The woman or queen holds a small child, who faces the viewer and is positioned next to her king. Together, the family encapsulates freedom with the child symbolizing freedom, which is the greatest treasure and a new start. Beckmann’s painting was thus a distilled version of the cultural context of Europe that was transformed from the darkness of everyday life into a message of light and hope in the face of political tribulation.

| Artist Name | Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix |

| Date of Birth | 2 December 1891 |

| Date of Death | 25 July 1969 |

| Nationality | German |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, New Objectivity, Dadaism, and Expressionism |

| Mediums | Painting and printmaking |

Another famous figure in the New Objectivity movement was Otto Dix, a renowned painter and printmaker, whose works captured the turmoil and anguish of German history. Dix witnessed both World War I and World War II, which left him with much to explore surrounding the dark social climate of Europe at the time. Following the First World War, Dix’s work explored the grotesque through social satire and exaggerated forms that reflected the styles of Neue Sachlichkeit and the ideals of artists from the Weimar Republic.

Otto Dix with a Paintbrush (1929) by Hugo Erfurth; Hugo Erfurth, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

From images of war-damaged soldiers to deformed faces, Dix emphasized the horrors of conflict and violence, which offered a new dimension in art that had not been explored as in-depth before the war. The dimension he referred to was that of “ugliness” in humanity and the ill parts of society that lay beneath a sense of false nationalism. Dix was also a skilled portraitist, even during the period when photography dominated war-era documentation. Dix painted many patrons of the arts from Germany, including members of Bohemian society and arts professionals.

Dix’s art was also associated with German Expressionism, which was inspired by his experience as an artillery gunner during World War I, where he witnessed first-hand, the “senseless violence” and bloodshed of war that he transposed into his paintings and printed works.

| Date | 1927 – 1928 |

| Medium | Mixed technique on wood |

| Dimensions (cm) | 181 x 402 |

| Where It Is Housed | Kunstmuseum, Stuttgart, Germany |

A classical piece of the Weimar Republic, Otto Dix painted this evening scene narrative across three panels that illustrate the height of Germany’s “golden twenties”. The nightlife of the Weimar Republic was illustrated through the presentation of luxurious elements such as the musicians to create a celebratory atmosphere and the ornate stand in a dance bar in the central panel. The women in the painting are also wearing dresses with designs that reflect Medieval designs and are decked with jewelry.

The panels were made cohesive with the inclusion of a couple dancing Shimmy in the middle and their bodies’ reflections caught in the parquet. The backdrop of the work is a dark shade of red while the left side presents several prostitutes positioned at the entrance of the bar. Two men were also included, one of whom was a disabled war veteran. Interestingly, the architecture in the right panel is distorted with themes of sexuality, decadence, and modernity entrenched throughout the composition.

The criticism of the painting was received with mixed reviews with harsher criticism coming from volkisch critics such as Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder and Richard Müller.

It is believed that Dix was inspired by several artworks from the Medieval and Renaissance eras with direct references to members of the Saxon art business. Metropolis was exhibited as part of a three-part series of shows for the 100 th anniversary of the Saxon Art Association. The woman dancing in the center was also identified as Dix’s wife, Martha Dix, while her partner is speculated to be the idealized version of the artist himself.

| Artist Name | George Grosz |

| Date of Birth | 26 July 1893 |

| Date of Death | 6 July 1959 |

| Nationality | German |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, New Objectivity, Dadaism, Expressionism, and caricature art |

| Mediums | Painting and drawing |

George Grosz was among the top three most famous Neue Sachlichkeit artists of the 20 th century, who went on to shape the movement alongside Max Beckmann and Otto Dix. Grosz was also part of the Berlin Dada collective and also had first-hand experience of the atrocities of the war while serving as a soldier. The German artist’s work revolved around social critique and invested in satirical illustrations aimed at supporting left-wing pacifist activities.

George Grosz, Berlin, (1930); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Grosz specialized in painting and drawing during the Weimar period to critique the “decay of German society”. The artist relocated to America to escape Nazi persecution and teach art since his work back home was regarded as “degenerate”. After he lost his faith in humanity, Grosz’s art style shifted from propaganda and caricature art to romantic scenes.

Today, his works are celebrated as iconic symbols of the German revolution that awakened the public to the oppression systems of the government.

| Date | 1927 |

| Medium | Rotogravure on laid paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 16.99 x 27.46 |

| Where It Is Housed | Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California, United States |

Maul Halten Und Weiter Dienen is a famous print by George Grosz, which is also recognized as “Shut Up and Keep on Serving”. The directness of the title was aimed at the bourgeoisie, who promoted the war once again while claiming to support peace, which Grosz criticized as blatantly hypocritical. The illustration also landed Grosz in trouble with the law and was held responsible on trial, alongside his publisher, for blasphemy. The image was created for Grosz’s set designs for the 1928 production The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk.

The illustration was included in a portfolio publication called Hintergrund (1928), which was issued on the day of the play’s debut. Grosz used a printing technique called photogravure, which was a cost-effective method to reproduce images. The drawing directly chastises Germany’s entrance into the Second World War using religious symbols to evoke anger.

His use of the religious icon Christ was leveraged as a tool for social judgment and critique, which reversed the traditional use of religious figures in European art.

| Artist Name | Christian Schad |

| Date of Birth | 21 August 1894 |

| Date of Death | 25 February 1982 |

| Nationality | German |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, New Objectivity, Verismo, Dadaism, and Expressionism |

| Mediums | Painting, drawing, and photography |

Famous German photographer and painter of the New Objectivity movement, Christian Schad was one of the most influential and innovative artists of the 1920s. Schad even invented his own approach to shadowgraphs and photograms, which are currently known as Schadographs. Schad’s works are housed in many globally renowned institutions, including the Neue Nationalgalerie and the Museum of Modern Art. His art career is understood to showcase a variety of media in smooth and realistic styles, including his Cubist and Futurist-inspired works of the 1920s, which were inspired by the paintings of Raphael.

Christian Schad (1912) by Franz Grainer; Franz Grainer (1871-1948), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Schad fled Germany in 1915 after a self-inflicted injury to escape his service in World War I. He later launched Sirius alongside his roommate Walter Serner, whom he lived with in Zurich. By 1919, he released his Schadographs on early photograms and emigrated to Vienna in 1927. It was here that his paintings reflected the styles of the New Objectivity movement and by 1930, he was invested in Eastern philosophy. His art production rate declined steeply after the stock market crashed in 1929, however, his works did not receive as much condemnation by Nazis as compared to other artists of New Objectivity. Researchers have also uncovered that Schad made plans with a Nazi in 1933 to enter the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

He later explored Magical Realism in his 1950s works and continued to experiment with photograms throughout the 60s.

| Date | 1929 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 125,4 cm x 95,5 |

| Where It Is Housed | Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany |

The Operation by Christian Schad is one of the most eerie Magical Realism paintings of the New Objectivity movement that illustrates a surgery rendered in the style of a 17 th -century painting. The composition includes a patient placed on a table and surrounded by many medical professionals who operate on his torso using various medical instruments.

The lack of blood in the image is what disrupts the scene and Schad only included a slight redness on an unknown organ in the patient’s torso. The stillness of the scene is eerie and carries a disturbing effect on the scene as a whole. Another disturbing feature of the painting is that one can spot the one eye of the patient slightly open, while the woman at the top rests her hand on his head. Her role is concluded to be one of a spiritual nature since her figure appears to emanate a halo of soft white, blue, and pink hues.

While Schad was not the most well-known and publicized figure of the 1920s, his work was later appreciated by many for his alternative approaches to photogram techniques and contribution to New Objectivity painting.

To summarize, the characteristics of New Objectivity art were based on the criticism of art and the attitudes toward the events surrounding it. Art classified as part of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement featured jarring colors and distorted forms. This art also included ideas of decadence, ornamentation, and complex narratives that reflected the chaotic context of social and political life in the Weimar Republic.

Actors (1942) by Max Beckmann; Max Beckmann, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

With a few elements borrowed from abstraction, art under this movement also emphasized the experiences of those who profited from the war, as well as those who were looked down on such as prostitutes and beggars. New Objectivity artworks also discuss themes related to sexual liberation, alienation, modernity, and other realities of the emerging era of the metropolis. An important point to remember about the movement was that it differed from a movement like Dada since it sought to capture the reality of the time, whereas Dadaism focused on questioning the idea of reality itself. In essence, New Objectivity art was strongly associated with an attitude of post-war cynicism, which saw many artists seek out satirical-based themes and Realism as tools to communicate their ideas.

These famous Neue Sachlichkeit artists and artworks offer us much insight into the golden twenties of the Weimar Republic, and the concerns of those who witnessed the effects of the World Wars firsthand. In studying these famous works and the styles of New Objectivity art, one can explore new useful techniques for approaching themes of social and political critique as they relate to contemporary reality.

The Neue Sachlichkeit movement is also known as the New Objectivity movement, which emerged in the 1920s during the Weimar Republic in Germany. The movement was a response to the art style of Expressionism and focused on the realities of the post-war period. Neue Sachlichkeit emphasized the rejection of romantic idealism and promoted the objective and functional aspects of reality. This included social and political criticism, pictorial art, narrative works, and two distinct groups called the verists and classicists.

There are many visual characteristics of art from the New Objectivity movement. These include an emphasis on the real world and a negation of romantic, ideal, and abstract representations that were previously found in Expressionism. Other characteristics include distorted figures, vivid colors, elements of ornamentation, modern narratives, decadence, sexual liberation, satire, and social commentary.

Among the many artists of the New Objectivity movement were Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and Otto Dix, who were considered to be the leading figures of the movement.

Jordan Anthony ( Content Editor, Art Writer, Photographer )Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.