The Death Penalty India Report (DPIR) was launched on 6 May 2016 and contains the findings of the Death Penalty Research Project (DPRP) which was conceived in June 2013, with an aim to address the glaring absence of empirical research on the death penalty in India. The DPIR is divided in two volumes. The first volume of the report contains quantitative information regarding the number of prisoners sentenced to death in India, the average duration they spend on death row, the nature of crimes, their socio-economic background and details of their legal representation. The second volume contains narratives of the prisoners on their experiences in police custody, through the trial and appeal process, incarceration on death row and impact on their families.

The DPRP was carried out with the extraordinary help and support of NLU, Delhi, in collaboration with the National Legal Services Authority, and under the careful guidance of experts such as Dr. Usha Ramanathan, Dr. Yug Mohit Chaudhary and Justice S. Muralidhar.

The motivation in undertaking this Project was to contribute towards developing a body of knowledge that would enable us to have a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the manner in which the death penalty is administered in India. While there exists excellent work on the analysis of judgments of the Supreme Court on the death penalty, there is unfortunately very little research on various other aspects of this extreme punishment. We were of the view that much wider research and its dissemination could significantly enrich the overall discussion on the death penalty and this Report is envisaged as a small step in that direction. A lot more work is certainly required on issues addressed in this Report along with identifying other relevant areas for death penalty research.

The Project interviewed 373 out of the 385 prisoners who were on the death row at the time and their families. Besides socio-economic data, the DPRP also documented accounts of prisoner experiences with police investigation, access to legal representation, experience at the trial courts, life on death row, relationships with family through the years in prison, and other associated aspects.

The various findings and observations documented in this Report were analysed from the viewpoint of prisoners currently under the sentence of death. In a historical sense, the analysis and information provided here then holds true only for a snapshot of prisoners sentenced to death in independent India.

The state of record-keeping we encountered during our work inspired very little confidence, if at all, about the feasibility of a broader historical analysis. Periodical research of this kind in the future would certainly contribute to developing trends concerning the issues identified in this Report.

At the core of this Report is our position that the death penalty is qualitatively a unique punishment, quite distinct from any form of incarceration. As is evident, this position is not a comment on the desirability of the death penalty as a form of punishment and neither does it primarily draw its strength from the argument that the death penalty is irreversible.

"India's death row prisoners face horrific conditions, study conducted by Death Penalty Research Project at the National Law University in Delhi".

THE NEW YORK TIMES

According to the national figures, 74.1% of the prisoners sentenced to death in India are economically vulnerable according to their occupation and landholding. Amongst the states with 10 or more prisoners sentenced to death, Kerala had the highest proportion of economically vulnerable prisoners sentenced to death with 14 out of 15 prisoners (93.3%) falling in this category. Other states which had 75% or more prisoners sentenced to death belonging to the ‘economically vulnerable’ category were Bihar (75%), Chhattisgarh (75%), Delhi (80%), Gujarat (78.9%), Jharkhand (76.9%), Karnataka (75%) and Maharashtra (88.9%).

23% of prisoners sentenced to death had never attended school. A further 9.6% had barely attended but had not completed even their primary school education. Amongst the states with a substantial number of prisoners on death row, Bihar (35.3%) and Karnataka (34.1%) had the highest proportion of prisoners who had never attended school. Kerala is the only state (amongst those states with 10 or more prisoners sentenced to death) where all prisoners had at least attended school.

While the national ratio for prisoners sentenced to death who did not complete their secondary education is 62%, states like Gujarat (89.5%), Kerala (71.4%), Jharkhand (69.2%), Maharashtra (65.7%), Delhi (63.3%) and Uttar Pradesh (61%) had a large proportion of prisoners under this category.

The educational profile of eight prisoners is unavailable. The category of 'Never went to school' (84 prisoners) is also included in the category of 'Did not complete Secondary'.

76% (279 prisoners) of prisoners sentenced to death in India are backward classes and religious minorities. While the purpose is certainly not to suggest any causal connection or direct discrimination, disparate impact of the death penalty on marginalised and vulnerable groups must find a prominent place in the conversation on the death penalty.

While the proportion of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (SC/ STs) amongst all prisoners sentenced to death in India is 24.5%, that proportion is signficantly higher in Maharashtra (50%), Karnataka (36.4%), Madhya Pradesh (36%), Bihar (31.4%), Jharkhand (30.8%) and Delhi (26.7%), amongst states with 10 or more prisoners sentenced to death. Religious minorities comprised a disproportionate share of the prisoners sentenced to death in Gujarat, Kerala and Karnataka. In Gujarat, out of the 19 prisoners sentenced to death 15 were Muslims (79%), while 60% of the prisoners sentenced to death in Kerala were religious minorities (five Muslims and four Christians amongst 15 prisoners sentenced to death). Of the 45 prisoners sentenced to death in Karnataka, 31.8% were religious minorities (10 Muslims and four Christians)

14 prisoners belonging to both other backward classes and religious minorities have been counted in both categories—‘OBC’ and ‘Religious Minorities’. Caste information regarding six prisoners is unavailable.

108 prisoners (30.2%) were economically vulnerable, had not completed their secondary education and belonged to the religious minorities or SC/STs.

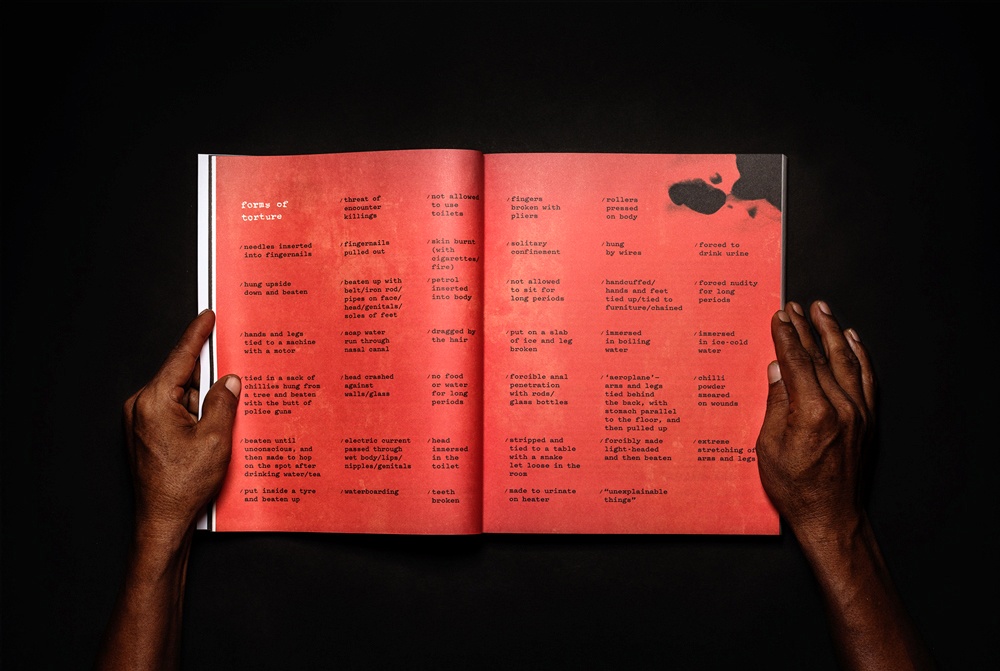

Volume 2 of DPIR undertakes a qualitative evaluation of the various processes that are used within the criminal justice system to administer the death penalty. Through narratives of prisoners and their families, the chapters on experience in custody, trial and appeals reflect the various crises points in the foundations of the criminal justice system.

Dr. Anup Surendranath

(Review, Analysis & Assistant Author)

(Project Design & Field Work)

Philarisa Sarma Nongpiur

The Death Penalty India Report (DPIR) was launched on 6th May 2016 and contains the findings I explain the project's purpose to a prisoner’s mother. “We are interacting with prisoners on death row across India and their families to understand where they come from, and what their experience with the legal system has been.” She gets scared and asks whether this means that her son will die. “No, no,” says her friend sitting next to us, “These people are here to help”. “Their research will ensure that no one gets the death sentence ever again, and the poor will not suffer.”She explains all this with amazing clarity, in a way that we couldn't have communicated to a scared parent. The friend herself is no stranger to the system since her husband was incarcerated as well. We are sitting in a four by four feet room, right beside a petrol pump in the middle of a slum. “This room is the only thing my mother has left me. My father died an alcoholic and so did my husband. Only my brother, God bless his soul, helps us. I have no one to rely on except my son.”

All of a sudden, she grabs my feet and begs me to save her son.“Even if he made a mistake, he should be given at least one chance to reform, don’t you think? How can you take away life? Will they hang him? Please madam, unko bacha lo.” She grabs my feet again and holds my hands from time to time, pleading with me to save her son and asking me if I think the death sentence is just; whether he will live or die. “Don't you think it’s wrong? Isn't it inhuman to take away life without giving him a chance to become a better person?”. Her eyes glaze over as she loses interest in our questions and she stares into space. We all sit in silence.

A Cacophony of CriesThere was no light in this part of the village and the entire affair took place using flashlights from a couple of mobile phones. Usually, we avoided visiting families at night, but in this particular situation, this was the only time we could have met her because throughout the day she would drag herself around town begging for food and aid.

In the village, the men beat her, the women abused her, and the children laughed at her. Ever since the incident, this had become a practice in the Musahari Tola (which belongs to the community of rat-eaters) of the village. There was nobody to support her, let alone help her. What was her fault? She was a mother, after all. Of course, she would defend her son; she would defend him even if he had committed the offence in front of her eyes. Was the society blind to her helplessness in this entire situation? Was it justified in meting out to her this brutal punishment –this utter disregard for human life and dignity?

Despite repeated attempts to talk to her, all she could mumble were a few words in a local dialect, which were beyond our understanding. Tossing around the floor in front of us, she seemed to have lost her mental balance and capacity to comprehend the nature of her surroundings. Time and again, she would gather strength and force herself into consciousness merely to be able to aim for our feet and shout out to us that, “He is innocent. These people are liars. Help him. I beg of you, help him, save his life.” She would then fall back, detached from the world once more.

Every desperate claim about her son’s innocence was followed by an outcry in the agitated crowd that had gathered in the courtyard of her tiny, two-room mud house. There were no less than 50 men and women, all highly intoxicated on a local inebriating drink called,tadhi–all of them looking to avenge crime against the victim, whose father lived next door. Our driver, being a local, was helping us understand the dialect, but he sensed the rising tempers and fled the scene five minutes into the interview.

This was our second trip to her residence. Our inability to find her in the morning made us return at night. This proved to be a disadvantage because information regarding our visit had reached the victim’s father, who had been waiting for us outside her house, along with an intoxicated and aggressive crowd. He wanted to ensure that we heard his account of the incident and hence, when we entered her house, everyone came along.

Although our task was quite clear –to locate the mother, interview her, and return –we spent another hour in darkness, a few kilometers off the road, trying to console the victim’s father so that we would not leave her worse off. The atmosphere had turned extremely tense and volatile, and we felt (although there were disagreements in the team) that hearing him out was the best we could do to help him vent the frustration and angst he carried in his heart.

When I recall the events of that day, I can never forget one of the women telling us why the prisoner’s wife, along with her son and daughter, had left. The victim’s father had threatened the family, “Jo usne meri beti ke saath kiya, woh mai uski beti ke saath karunga. Tabhi usse ehsaas hoga ki kya kiya hai usne, aur tabhi jee paunga main (I’ll do exactly what he did to my daughter to his daughter. Only then will he realize what he has done and only then will I be able to live in peace).”

None of us uttered a single word on our four and a halfhourjourney back. Despite the fact that we did not get an interview that night, all of us took back something more –an understanding of how society functioned; its need for revenge. And over the course of the project, this understanding was only concretised.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter who pays the price or who gets hanged, it doesn’t matter if they deserved it or not, it doesn’t matter whether the crime rate is actually being controlled or not, what matters is that someone is paying the price, someone is getting punished,someone is getting hanged. As long as they are, society rests in peace, unperturbed by the justness of justice.

None of us slept that night.

The Cycle of MarginalisationIt’s a strange feeling, to meet someone you have read about. One feels an odd sense of familiarity, even while there is none. We were faced with this sentiment when we interviewed a prisoner’s family. We had to be escorted by the police, since they claimed that the area was extremely sensitive. There seemed to be the suggestion that these were the kind of people we required protection from, that they were dangerous.

It is sad that people are labelled since these labels are, most often, enormously devoid of truth, as was the case with this family.

When we first saw the family, they were feeding the cattle. Their kuccha house had two small rooms and absolutely no furniture. This was one of the poorest families I had ever met. The prisoner’s mother was wearing a sari without a blouse; she had managed to drape her sari in such a way to cover her chest as well.

While the interview started off with the prisoner’s wife and mother, soon, the entire family joined us.

Speaking to them, we found out that they had no resources to sustain themselves, let alone go and visit their family member in jail. The case was more than 20 years old and they had had a very harrowing time. Yet, they said they had hope.Hope for his return.

It is said that hope that lingers can keep one going for a long time and is one of the strongest feelings one could ever experience. This family, in a small, remote village, was experiencing a phase in their lives that few could have survived. Most would have given up or ended their lives.

They told us that the convict has been in jail for 20 years and they wanted him to come back home. These words from the convict’s wife,“It is the kind of pain that never goes away,”might sound weak to most people, but for a family which has to worry each day about how to put the next meal on the table, it is a harsh reality. A nightmare for some is a reality for others. The extent to which the absence of an earning member can affect a family wasright in front of us.

Throughout the interview, the police constantly interfered, and wanted everything to be hushed up. The prisoner’s wife told us that the police had tortured the family a lot. It is upsetting how the institution of the police, even though subjected to procedural safeguards, exercises blanket powers and misuses its position of authority in many areas.

When we talk about these death row convicts, hardly any description of the condition of the family members and their struggle is ever shared with the world. Instead, these people who don’t have enough resources to stand for their innocence or fight for justice are labelled as hard-core criminals.

People who have all the amenities and yet complain because an extravagant lifestyle has become a necessity, and a family that survives on nothing but hope are like the two extremes which will never meet, each unaware of the life the other leads.

Who is to be blamed for this? The police, the state, the lawyer that never bothered to speak to the family or the convict to know more about the case, or one’s own financial situation, which was so imbalanced that one couldn’t afford a lawyer to defend the case? The blame game continues and will continue and an inference could be drawn looking at these 20 years of pain and suffering.

Greasing the MachineryThis was one of the most uncooperative prisons I had ever been to. From making us wait for hours before providing access to the prisoners despite having all the permissions to frequent interruptions during interviews and insisting on deputing prison staff who would be able to hear everything that is said during the interviews, being there was a nightmare. Moreover, most of the officials were terribly rude.

All the prisoners told us that there was a lot of corruption and abuse of power in this prison. It was not very difficult to believe, however, it didn’t really strike us till we reached the end of our visit. There was one prison official who guarded the main gate to the prison. Every day, he would greet us and exchange a few pleasantries with us as we entered and exited that dreadful prison. He seemed like an aberration in an environment of corrupt officials who seemed to be doing everything in their power to make our work more difficult.

As we were leaving, deeply disappointed with our experience, we met him at the gate. He asked us if we were leaving already. We told him that thankfully, we were heading back to Delhi. He said, “Then give me a party.”This was a surprise. We didn’t quite understand what he meant so we asked for clarification. He smiled and said, “A Rs. 500 note would be nice.”We looked at each other and then at him in disbelief. He couldn’t have just asked us for money, could he? He said it again, just to make sure that we understood him right. We refused and walked on, still recovering from what we had just heard.

What did it say about the state of this prison’s administration that we were being asked to pay money for absolutely nothing? It made me wonder, and I shuddered to think, about how he would treat the family members of the prisoners who come for visits, people whose entry to the prison depended completely on his will. It was a cruel insight into the working of a prison. He wasn’t hesitant and he wasn’t scared of the consequences of his actions, because he knew that there wouldn’t be any.

The Noose that DangledI watched him smile. It was a gentle smile. His skin was dark, burnt almost. And woven into its burnished brilliance were creases that chased one another, weaving a tapestry of pain. “My childhood,” he said, “was filled with games of galli-danda and marbles”. His hands and legs shook as his brown eyes possessed a peculiar numbness - a numbness that was somehow rimmed with understanding and they looked into mine, and he said that he wouldn’t be able to walk to the gallows. He spoke of a noose that dangled menacingly and a noose that dangled beckoningly.

The stories may have been different because the voices are different - in the subtle inflections, in the differences in pitch, harmonizing to create music that sings primarily of pain and poverty, but which also sings of the unabashed whimsy of a system that claims to be fool-proof, which proclaims its ability to bring justice to both the victim and the perpetrator, but which does neither.

One of the reasons I was doing this was for myself. I was doing this to better understand the terms that are so frequently used in popular discourse - caste oppression, gender inequality, intolerance, and economic oppression. Terms that have now become so much more than mere words and phrases.

An instance that comes to mind is a visit to a village in Karnataka. While I was always aware of caste shaping our lives and our daily interactions insidiously, I had never truly understood just how much power it could wield. In Karnataka, in a nondescript village that was a two-hour drive from Bangalore, caste was not merely manifested in ‘naavu’ and ‘avaru’(us and them) as was in the rest of the state, but in a tangible, taut tension – a heaving river that threatened to spill over and devour in its tempestuous wake the invisible constraints that bound the residents of the village to their fragile peace. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that these experiences have provided me with a better understanding of the issues that plague our nation and the system. But I could say that my experiences have provided me with a better understanding of my own ignorance.

This project has helped me forge bonds with people I would never have otherwise closely interacted with, providing me with an array of people I could filch food from. The project taught me to brave bathrooms with malfunctioning flushes, led to a significant improvement in my Hindi, and taught me that waiting list 54 is probably not the best risk one should take. It has also made me more aware of my position of privilege, including the fact that I could easily return to the world of air-conditioning and plush chairs, and that it is only a quirk of fate that has led to this stark difference between me and those on the other side.

In that rickety bus, I sat thinking about why I was a part of this. Was it because I was learning about the criminal justice system, being made more aware of the flaws that are deeply entrenched in it? Was it because I was learning to survive in inhospitable climes, or was it because I knew that this was an opportunity to experience something I, in all likelihood, may not be able to avail of again?

The wind slipped in through the gap between my shawl and my skin. I shut my eyes and I could see Him again. Him with the dark skin and saffron turban.

For a minute, I was him, and I could see, in a hazy, confused, blur, the khaki-clad policeman, swooping in in the dead of the night, the thana where they hurt me in unmentionable places, where I pressed my inky thumb against sheet after sheet of blank paper, the court where the ‘judge-saab’ muttered unintelligibly in a language I didn’t understand, the faces of my family etched into my brain as I waited for them to visit (they never did but I couldn’t blame them), the bewildering procedures and the trials and the grimness of the courtroom, the nice lawyer who promised that I would be out in no time but who would, every month, with a wry, thin-lipped smile, ask me for a couple of thousand rupees; I even thought of the newspaper clippings that I had saved. They thought I was a monster, eyes flashing with bloodlust, with calloused hands and long, dexterous fingers. I thought of the grey confines of the jail, where the only solace I derived was from chanting hymns dedicated to a God I wasn’t sure I believed in.

And I pictured his knock-kneed limbs collapsing beneath his frail, hunched body as he walked to the gallows. I saw a rope, hewn with dry hemp, nibbling into the nape of his neck, and then gnawing with the famished fury of a society that longed for blood. And glistening against the colorlessness I could see the gimlets of his blood and the blood of the woman he said he hadn’t raped – both leaving the same slightly metallic aftertaste.

Again, I could see the noose dangling menacingly and the noose dangling beckoningly. And I suddenly knew who I was doing this for.